Curious Kidnapping of Laura Ellis: A little-known 1930s saga

By Diane Euston

Kidnappings in Depression-era America were so common, some public officials wondered if they should be called an epidemic. Most local crimes of this sort somehow involved politics.

The kidnappings of Mary McElroy and Nell Donnelly in the early 1930s captured headlines across the nation and were linked to the corrupt “Democratic Machine” in Kansas City. The highly publicized kidnapping of Charles Lindberg’s infant son in 1932 led Congress to pass the Federal Kidnapping Act. This authorized the FBI to get involved in kidnapping cases, and it also allowed for federal involvement when a victim was taken across state lines.

This new act came into play in 1934 when a middle-aged beauty shop manager vanished from sight after attending a labor meeting at 14th and Woodland in Kansas City. She was found dazed and confused hundreds of miles away, but the incident remains mysterious. Was she kidnapped? Was she mentally unstable? Was she a con artist? Police, family members and friends were left scratching their heads.

Laura Catherman’s Early Controversies

Born in 1885, Laura Catherman was the second oldest of five children. Her father, Frank, worked for the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad. After growing up in Newton, Kansas, his job transferred him to the Argentine area of Kansas City, Kansas.

It was said that around 1902, Laura suffered a head injury at a roller-skating rink. “Since that time, she has experienced a lapse of memory,” the Kansas City Times reported.

An injury to the head didn’t stop her from being active in controversial activities; she was an active suffrage worker, and while in school in Kansas, “She led the girls of her school on a strike for separate schools for whites and negroes.”

In 1909 Laura was found by her sister, Clara, unconscious on the floor of their home. She had been alone and claimed she was attacked by two burglars who struck her three times and stole $10 from her. When examined, her head wounds were found to be consistent with the end of a club or the butt of a revolver.

The burglars were never found.

In 1914 Laura worked as a cashier and telephone operator at the Pullman Hotel at 12th and Locust. The owner was shocked to discover Laura had stolen money from the cash register and from guests. Laura told her that she was desperate due to poverty and a sick sister; her boss didn’t call the police.

It wasn’t long before the law caught up; her main victim was none other than her father. When the 29-year-old was arrested in December 1914 for check forgery, she repeated the story that poverty and a sick sister had led her to the crime.

Her father said that wasn’t true. In fact, Laura had been managing his own savings account for years. He handed over every paycheck to her for deposit, and had the bank book to prove it.

Further investigation showed the bank book was a forgery, and a rubber stamp and an ink pad were found in her bedroom. She had stolen over $5,000 from her father.

John C. Ellis, a boarder living with the Catherman family, then came forward and said his own bank account was short $100.

The more police investigated, the more they realized that Laura’s actions were beyond deceitful, however, her behavior at police headquarters was bizarre. She didn’t know her own name and often broke down in fits. They transferred her to General Hospital where she was “subject to hallucinations and hysteria” whenever police interviewed her or mentioned the missing money.

In January 1915 Laura was put on trial for one count of check forgery. Some suspected she had hidden the stolen money in a downtown safety deposit box or buried it. Others couldn’t imagine this and maintained she was “a girl of inexpensive habits and modest tastes and ambitions.”

In February she was found not guilty by reason of insanity and sent to St. Joseph State Hospital for treatment.

After just a few months, Laura was released from the hospital and married the boarder, John Ellis, who once suspected she stole money from him. They moved to Omaha, Nebraska, and had a daughter named Georgia.

Lee Vaughan’s Labor Union Troubles

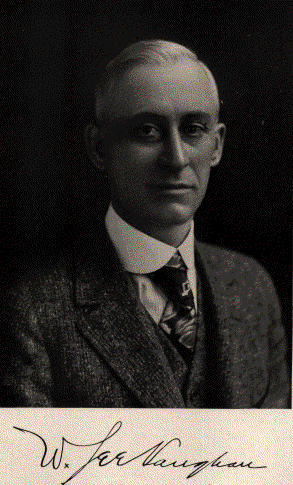

Laura returned to Kansas City, Kansas, presumably after her husband died, sometime in the 1930s and settled near her family. She found lodging with local businessman W. Lee Vaughan, a widow with four children, whom she likely met through her brother-in-law.

Vaughan was a well-known banker and prominent member of the Chamber of Commerce. He also owned several theaters, and in 1928 began to have troubles with the local Moving Picture Operator’s Union. He had hired union workers to operate the projection and sound at his theaters, but over time, they demanded more money. As sound pictures grew more common, the union insisted on two operators in the booth – one for projection and one for sound.

Vaughan disagreed,noting one man could do both jobs. The dispute landed him in court, where records indicate that union workers were constantly making threats, “followed by a series of acts of vandalism, intimidation, sabotage, and willful destruction of [Vaughan’s] property.”

His two theaters in Missouri, the Neptune and New Center, were bombed more than once, and he found it safer to operate business on the Kansas side as labor disputes and threats continued.

The Mayflower Beauty Shop

Just down the road from his Art Theater at 1806 Central Ave. was the Mayflower Beauty Shop. Laura had found employment managing the business, and now lived above the shop with her daughter.

In September 1930 she got into trouble when two agents from the Kansas State Board of Cosmetology entered the shop and asked to see the operating licenses of the ladies working. One woman named Hilda Hawley was missing a license, and it was said that both she and Laura were arrested after assaulting the agents.

A week later Hawley marched into the beauty shop with an unidentified man and woman and locked the door behind them. A witness stated that Hawley pulled out a club hidden within a newspaper, beat Laura over the head and then choked her.

When the witness tried to intervene, she was held back by the man, who said the women should “fight it out.” Screams alerted neighbors as Hawley and her accomplices jumped into a Buick and sped away. The assault was apparently due to the fact that Hawley had not been paid for her work.

When the police caught up with Hawley, she denied hitting Laura with a club. The Kansas City Star reported, “She said Mrs. Ellis struck at her at first with a curling iron and she retaliated with a blow from her fist.” Laura was treated for two fractured ribs, and Hawley never faced any charges for the incident.

Laura continued to operate the Mayflower Beauty Shop as she maintained her friendship with Vaughan.

Threats Lead to a Kidnapping

Vaughan continued to have issues with the labor union, and it’s likely he entrusted Laura. He refused to put union workers in the booth at the Art Theater, and threatening letters were sent to his daughter and Laura.

In March 1934 Laura was asleep in her apartment above the beauty shop when she woke to smoke and fire in the hallway. Flammables had been piled up and intentionally set on fire. This sounded quite familiar to Vaughan, who had suffered from several fires and bombs in his theaters. Was Laura being targeted due to their friendship?

Three months later Laura attended a recital at Northwest Junior High School and then drove her Dodge automobile to the Labor Temple at 14th and Woodland. The newspaper reported she went there to gather information for a friend who operated a “picture show” and had ongoing labor disputes with the men speaking there.

Laura later described how she left in her Dodge and was forced off the road by a truck with three men who “strong-armed” her before disappearing from the city.

Two typed letters were sent anonymously to Vaughn and Laura’s sister, Clara. One letter listed the location of Laura’s car, which was found filled with rolls of tape perhaps used to bind the victim. The letters were signed by “The Big Three,” and below the signature were the words, “And we mean big.” There was no ransom demanded, so the FBI wasn’t involved. The police believed Laura was kidnapped over the ongoing labor disputes, and Vaughan felt responsible for the unfortunate event.

Two days later Laura was found 350 miles away on the side of a residential road outside Decatur, Illinois. Described as “dazed and confused,” she was placed in a local hospital. When questioned, she claimed to remember little and said she had been injected with narcotics. Police did see needle marks on her arm.

Laura’s Story Questioned

Escorted by her sister, Laura returned home, where she claimed a nervous breakdown and refused visitors. “She will be alright in two or three days and will have a statement to make,” her sister announced as she shut the door on investigators.

Days went by and Laura still had not made a formal report with police. Jack Jenkins, chief detective, proclaimed that until there was a report, no action would be taken. “As far as the department is concerned, Mrs. Ellis never has been kidnapped,” he declared. “There has been no information from any authoritative source which would provide that deduction”.

The next day Laura was ready to tell her terrifying saga to the newspaper–not the police. After retelling her kidnapping, she linked it to the ongoing labor disputes her friend W. Lee Vaughan had been through. She even claimed that a year prior, three men and a woman came into her apartment and threatened her, demanding she make a statement to defame Vaughan. She refused.

“There is no man in the world for whom I have greater respect or deeper affection than Mr. Vaughan,” Laura told the Kansas City Star. “And our friendship has resulted in unbelievably physical and mental torture for me.”

At the end of the interview she said she wouldn’t allow hoodlums to interrupt her friendship.

Just one month later, Laura reported she received a letter that she and Vaughan needed to stuff a shoebox with $3,000 and deliver it to “The Big Three” at a named café. Federal agents watched closely as Vaughan and Ellis waited for the men; no one showed up.

Agents were starting to doubt her stories.

An Attack and a Hoax

On Aug. 3, the Kansas City Star reported that Laura was found dressed in her nightgown, gagged and tied to the refrigerator in her apartment with her eyes covered. Her hair had been cut off close to her head and was “stuffed into a sack.”

She was taken to the hospital and was found unharmed minus her missing hair and a few bruises. But she was “in a hysterical condition and unable to give a clear account of the attack.”

A note mentioning Vaughan was found on a table and said, “Tell your Uncle Sammie we are about 100 miles south of here.” It was signed “The Big Three.”

Due to the complexity of the cases involving Laura and the fact she was taken over the state line, federal officers were put to the task of getting to the bottom of the story.

It didn’t take much for her to confess a few days later that “all the threatening letters she had received, the complaint that her hair had been cut off, that she had been beaten, that she had been given narcotics and kidnapped, were part of a hoax.”

One federal agent noted, “Mrs. Ellis asserted she did it all because of her love for W. Lee Vaughan.” She claimed she was afraid that if he didn’t make the demands of the labor union, he would be harmed.

Headlines were not friendly when investigators openly told the press everything she had reported was “a product of her imagination.”

Her despair was about to turn into real tragedy.

The End of Laura Ellis

The day after confessing, 49-year-old Laura was nowhere to be found. Employees at the Mayflower Beauty Salon told agents she couldn’t stand the negative publicity and had left work Saturday afternoon. On Sunday, Sept. 9, 1934, a couple searching for a rental home visited a property at 2001 N. 18th St. in Kansas City, Kansas. As they walked near the driveway, the woman noticed a person’s feet dangling through the half-open door of the garage.

The couple found Laura dressed in her underclothes with “an old-style .32 calibur revolver beside her outstretched hand.” Her dress and purse were hanging on a nail near the door. She had shot herself through the heart.

The only note she left was for her 16-year-old daughter. It simply stated she would be gone for some time and she should go live with her Aunt Clara. When Vaughan was told of the suicide, he said, “I don’t care to discuss it.”

Many Questions Left Unanswered

In midst of so much political mayhem in the 1930s, Kansas City was host to multiple kidnappings–some true, some false.

The story of Laura Catherman Ellis is certainly heartbreaking and full of unanswered questions that will never likely be answered. Was Laura “insane?” Did she suffer from mental illness from her fall as a child? Was she just seeking the attention of the man she loved?

We will never know, but these captivating stories open our eyes to the goings-on in Kansas City at the heart of when corruption conquered the politics of the city.

Diane writes a blog of the history of the area. To read more of the stories, go to http://www.newsantafetrailer.blogspot.com.

You may also like

-

Curious about your home’s history? Kansas City Public Library has a boot camp for that

-

John Perry and the tragedy of La Bourgogne

-

Breaking Barriers: Emery, Bird Thayer’s Female President, Annie Bird

-

One of the Many Unsung Heroes of the Civil War

-

Taking Up the Black Man’s Burden: The Life of J. Dallas Bowser