By Diane Euston

When thinking about the early growth of western Missouri, it’s hard to ignore the importance of the Santa Fe Trail. In Independence, Mo., three trails intersected. Businesses outfitted daring pioneers, businessmen and traders passing through the desolate landscape.

Because Missouri was a slave state, these early settlers of Missouri – predominately from Virginia, Kentucky and Tennessee – brought with them enslaved men, women and children. One enterprising, talented man was able to buy his own freedom and become one of the wealthiest men in all of Jackson Co., Mo. His business sense and savviness crafting wagons and yolks in Independence places him at the top as one of the most celebrated early African American success stories.

Even with a long life full of prosperity, Hiram Young’s life is still much of a mystery. What was written about him occurred years after his death, and accounts of him are drastically different.

Hiram Young opens our eyes to the enterprising spirit of so many pioneers at the time, and his rise from slave to industrialist is a story worth retelling.

The Rise of Independence

200 years ago in 1821 – the same year Missouri became the 24th state, Mexico won their independence from Spain. This opened up commercial operations between Mexico and the United States. In that year, William Becknell began making trips from Franklin, Mo. to Santa Fe. Becknell, hailed as “the father of the Santa Fe Trail,” mapped out the safest 900-mile route for travelers.

Just four years later, Senator Thomas Hart Benton was able to get Congress to appropriate money to survey the route and negotiate treaties with Native American tribes to make travel even safer.

In 1827, Independence, Mo. was founded along the trail route approximately 100 miles east of the starting point of Franklin. In 1878, John C. McCoy (1811-1889), founder of Westport and Kansas City, wrote, “There was an ancient, well beaten Indian trail leading from [Fort Osage] westward, following very nearly the line of the present traveled route through Independence to the state line near Westport.”

Independence fell on this old trail route and was conveniently located just four miles from Blue Mills Landing where steamboats could drop off travelers. At the time, it was the westernmost landing on the Missouri River and at its founding, everything to the west of Independence was wilderness.

In 1838, a man named William McCoy (1813-1900) and his brother came to Independence from Ohio. One brother wanted to make their home in St. Joseph while the other thought Independence was their best bet. The decision was made with a coin flip – Independence won the toss. The brothers established a mercantile store on the Square. By the 1840s, William McCoy was a partner in Waldo Hall & Co. that traded with Native Americans and Santa Fe.

Independence was incorporated in 1849 and boasted a population of 900. The first mayor of Independence was successful business owner, William McCoy.

Before Independence: Hiram Young’s Complicated Life

To state there is factual information pertaining to Hiram Young’s early life is an understatement. What is rarely disputed is that he was born around 1812 in Hawkins Co, Tenn. Some state he was owned by a man named Walton.

By around 1845, Hiram was brought from Tennessee to Greene County, Mo. His owner at this point is disputed in the various accounts (in some records he was said to be owned by a man named Judge Sawyer and others state is was a man named George Young), but what isn’t disputed is that after he completed his tasks as a laborer, Hiram was allowed to work for his own wages. In a short amount of time, he showed “unusual skill as a mechanic.”

Nearby was a young, beautiful slave named Matilda Huederson (c. 1824-1896). Hiram married her. With the money he saved up, he was able to purchase his wife for $800. Accounts indicate he purchased her before he was able to secure his own freedom. This could have been the case, because any children born to her would be enslaved and would follow the condition of the mother.

Whoever his master was, he must have been easygoing as Hiram continued to work for his own wages and eventually purchased his freedom for $2500. Shortly thereafter, he removed to Lafayette County and later Liberty.

Around 1850, Hiram Young moved to Independence, Mo. His choice of Independence was likely no mistake; his talent of whittling wood and working as a mechanic was a perfect combination for a town built on the trails. Around this same time, Hiram and Matilda welcomed daughter Amanda Jane Young.

The Rise to Riches

Standing at about 6’3” with a light-copper complexion “with a large mouth, fairly thin lips and an usually high voice for a large man,” Hiram Young was starkly different than other enterprising men of the town. In 1850, he was one of only 41 free blacks in Jackson County where 2,969 slaves and 10,990 whites lived. Laws at the time indicate the environment in which Hiram Young lived. In 1849, Independence issued a city ordinance that stated that slaves could not assemble in groups over six people, and in 1857, they banned “negroes or mulattos” from gathering for religious purposes.

This shows the tremendous hill Hiram Young, a free black man, had to climb. His first home on the outskirts of Independence was said to have been a log cabin “without any door” deep in the woods; in order to keep out the cold, they had to hang animal skins along the walls.

In 1850, Young didn’t yet own property and was working as a carpenter. Within a few short years, Hiram’s reputation making ox yokes and wagons for travelers along the trail had grown enough for him to purchase a property covered with trees; he used the wood for his factory. It was said that he “could neither read nor write, but people who knew him say he could look at a tree and tell you how much lumber it could produce.”

His shop stood on the northeast corner of current-day 24 highway and North Liberty St. and quickly became one of the most successful outfitting operations in all of the county. It was said that “every emigrant train stopped at Independence long enough to refit and purchase schooners and ox bows from Hiram Young.”

Within the early days of his business, he was manufacturing yokes and wagons used mostly for government freighting. These freight wagons made for the Santa Fe Trail, branded with “Hiram Young and Company” were designed to be pulled by six teams of yoked oxen and could haul 6-8,000 pounds. Because he couldn’t read or write, William McCoy who served as the first mayor of Independence assisted Hiram with his books for years. Hiram built a large brick home across the street from his business and owned a 480-acre farm east of Independence in the Little Blue Valley. As his business grew, he added a diverse group of employees which included both whites and slaves.

The accounts of his treatment of enslaved people drastically varies. Some stories shared over the years state that when his business burned down, he sold his wife and daughter who he had not freed back into slavery to raise funds. Another unsourced article from 1891 said he fell in love with an unnamed slave, purchased her, had several daughters with her and moved her into his plantation home with his wife, Matilda where “thereafter his domestic life was anything but peaceful.”

What is known is that Hiram Young did own three slaves in 1860, but his reasons for this are explained in various accounts. He often would buy families of slaves so they would not be separated and, like his own master did, allowed them to work for their freedom. At his death, the Wyandotte Gazette wrote, “Before the war he, though himself a negro, owned slaves, among who were Riley Young, his own brother, old aunt Lucy Jones, Wesley Cunningham, and others well known in Wyandotte.”

Research confirms that these formerly enslaved people all lived together in Quindaro and then Wyandotte, and Riley Young – listed as a yoke manufacturer in 1865 and a carpenter in other records – could very well be Hiram’s younger brother. Confirming whether these men and women were the property of Hiram Young is next to impossible to confirm, but my research does show there it is likely that they did at one time prior to the Civil War work for the industrious wagon manufacturer of Independence.

By 1860, Hiram employed between 50 to 60 men at his shop on his farm and 20 men at his shop on Liberty St. where a four-horsepower steam engine and seven forges ran around the clock. His business inventory at the time was worth over $50,000 and he was turning out between 800 and 900 wagons per year.

This wealth wasn’t just impressive for a freedman – he was one of the wealthiest men in the entire county. Hiram even described himself as “a colored man of means.” His reputation within the community was well-respected by people of all races, and he was described by those who knew him “as a man not only of extraordinary intelligence and energy, but of unwavering integrity.”

The Civil War and Following Years of Struggle

Due to tensions along the border, Hiram Young moved his wife and daughter with him to Fort Leavenworth, Ks. around 1862. There, he could continue to fulfill government contracts making wagons. He opened a blacksmith shop and wagon manufactory that operated until 1868.

While in Leavenworth, Hiram became involved in politics at the close of the war. Although possibly surprising, he was a Democrat, and the Republican party was founded, among other issues, on the principle of abolishing slavery.

In 1868, he was chosen to speak at a public meeting for Blacks to advocate for the Democratic Party. On the day of the speech, an old man passing by asked him about his Democratic views, and an Irishman passing by overheard Hiram’s impromptu speech. Although the Irishman shared Hiram’s political views, he seemed to be upset a freedman shared them. The Irishman used a stone hammer “and dealt a forcible blow upon the Democratic orator.”

Hiram was carried home and unable to give his much-anticipated speech.

While living in Leavenworth, Hiram befriended a minister of the African Methodist Episcopal Church named Hiram Revels (1827-1901). Hiram Young had attended a conference and wanted to establish a church back home in Independence, and Hiram Revels agreed in 1866 to help establish the St. Paul AME Church and served briefly as his its first minister. Revels moved to Mississippi and was elected as the first African-American senator in 1870.

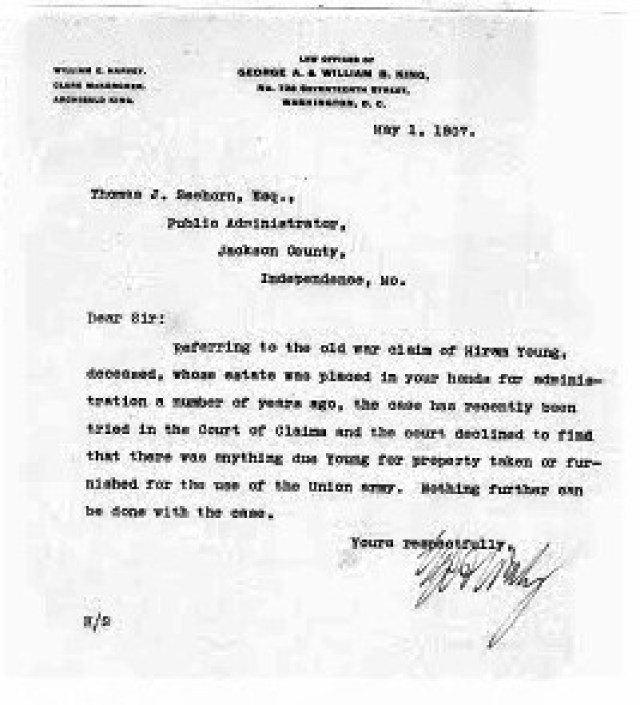

Even as a church was established with the help of Hiram Young, his business was not faring well. When Hiram returned from Leavenworth, he found the Union Army looted his property and had taken 7,000 bushels of corn and 37 wagons (valued at $250 each). In total, Hiram sued the government for losses of $22,100, and the case was held up for years. In 1907, the claim was thrown out.

In 1873, Hiram’s business, machinery and tools were destroyed by fire. He was insured for $2500, but the losses totaled well over $6000 and left 20 people unemployed. Hiram was so well-respected that the community came together to help him replace the steam engine. The Kansas City Times wrote, “This is nothing but right. His loss was quite heavy. . . Our citizens can well afford to contribute something towards this laudable enterprise.”

Hiram understood the importance of a good education, as he wasn’t afforded a day inside a schoolhouse. He sent his own daughter, Amanda, to Oberlin College. In 1874, Hiram helped raise $4000 to build a two-story brick school for eight grades for black children. It was named Douglass School after Frederick Douglass.

Due to the decline of wagons because of the arrival of the transcontinental railroad, Hiram’s new business was a three-story brick factory used as a planing mill full of woodworking machinery. By 1880, he had eight employees working 10 hours a day. Although it never grew to be as successful as his pre-war wagon business, Hiram was able to maintain a comfortable living.

Hiram’s Death and Legacy

On Jan. 22, 1882, Hiram Young passed away with only a fraction of his prior wealth. The newspaper reported, “As a special mark of the respect in which he was held, his body was buried among the white people [at Woodlawn Cemetery].” In that same year, the Douglass School was renamed in honor of Hiram Young. The school is no longer in operation.

As her husband’s assets were held in probate, Matilda Young was left “with no grain, meat, vegetables, groceries and other provisions in hand.” Once again, the community stepped up; their old friend William McCoy loaned Matilda and daughter, Amanda money to survive.

After his death, the factory closed and the family held onto the few lots they owned. Matilda died in 1896, leaving what was left of the property to her sole heir, Amanda. Amanda married and taught school in Independence and Kansas City. She even spent time at Lincoln High School and lived in Kansas City up until her death in 1913.

In 1987, Lexington Park in Independence was renamed for Hiram Young along with a portion of the street leading up to it. In 2011, the new Red Bridge over the Blue River included 10 columns featuring 10 trailblazers along the Santa Fe Trail – one of them represented is Hiram Young. One year later, a decorative panel describing Hiram Young’s life, aptly placed at McCoy Park (named after his longtime friend and business agent) in Independence, was added to tell his unique story.

Hiram Young broke down barriers well before many were comfortable with equality for all. He was the definition of a pioneer – he was willing to take on the scrutiny of being one of the only freedmen in Jackson Co. and built up a business that outfitted travelers throughout North America. It was said at the time of his death, “His goods are scattered from Texas to British Columbia and from the Mississippi to the Pacific Coast.”

Although his fine craftsmanship has all but disappeared, Hiram Young’s story is retold throughout the nation and will stand as a legacy for years to come.

Diane writes a blog on the history of the area. To read more of the stories, go to www.newsantafetrailer.blogspot.com

Diane will be speaking about Hiram Young and other trailblazers at the Trailside Center’s celebration of the bicentennial of the Santa Fe Trail on Sept. 18 at 2:00pm. More information will be provided soon!

I was hoping that you would write about him. I knew some of his story, but not this many details. It is a story that needs to be told. Not a perfect man, but a man who did much good in a horrific time. You are such a great researcher and storyteller.